Africa.com’s Teresa Clarke joined the roundtable discussion

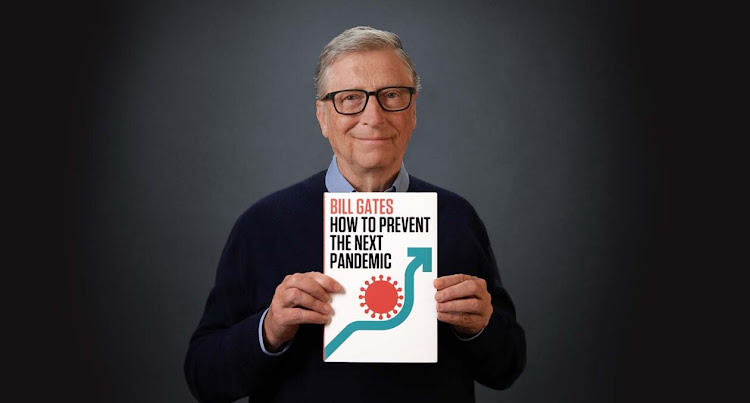

Philanthropist Bill Gates believes we can prevent another pandemic from killing millions of people and devastating the global economy. In his new book titled How to Prevent the Next Pandemic, he lays out clearly and convincingly what the world should have learned from COVID-19 and what all of us can do to ward off another disaster like it. Relying on the shared knowledge of the world’s foremost experts and on his own experience of combating fatal diseases through the Gates Foundation, he first helps us understand the science of infectious diseases. Then he shows us how the nations of the world, working in conjunction with one another and with the private sector, can not only ward off another COVID-like pandemic but also eliminate all respiratory diseases, including the flu.

Bill Gates answered questions from a select group of African journalists during a roundtable that took place on Thursday, 28th of April.

INTERVIEW

MODERATOR QUESTION: When and why did you decide to write the book, How to Prevent the Next Pandemic?

BILL GATES: Well, the COVID pandemic has been an incredible tragedy, with the costs, and you have economic damage. You have tens and millions of deaths. You have education opportunities lost. It’s been a very tough, tough two years. For many countries, they’ve had more deaths than they had for anything since World War II. And so you’d hope that the world would pull together and think, okay, how do we prevent this from happening again.

If you look across different countries, some did better than others. Australia, for example, has less for example, has less than 10% of the deaths of most of the upper income countries because they acted very quickly. Japan has a lot less deaths because they are one of the best countries at wearing masks in the world.

And so we should step back from this incredible tragedy, look at what went well and think through how do we respond quicker? And that’s where the idea of a global team, which I call GERM (Global Epidemic Response and Mobilization) that comes in, and what tools should we have had. And hopefully people don’t forget that, even before the pandemic came, although there’s been incredible progress in reducing health inequity, year after year, the inequities in access to health treatment are pretty stark between developing countries and upper income countries.

The foundation is one of many organizations that works on that, and sadly, the pandemic has not been an exception to that. But hopefully it reminds people we need to do more, including strengthening health systems.

MODERATOR QUESTION: But is it too early to start thinking about future outbreaks when we’re still fighting COVID?

BILL GATES: Well, because the world doesn’t have global government, we work through these UN organizations, including the WHO, and the process of adding a new capacity at that level and making sure that it’s well funded and well-run takes time. I think it’s important for both the research agenda, some of which is going to take 5 to 10 years for that global capacity, which always takes time to get into place and get the right consensus and funding. And for highlighting the inequity, I think while this is still in our mind, that’s when we really ought to have the debate. And so I thought having the book come out with a proposal, some thoughts about what GERM should look like, what the R&D agenda should look like, and a reminder about the central role of health systems – you know, I thought it was very timely.

It’s absolutely true. This pandemic is not over. New variants will come along. How severe they will be is hard to predict. The entire world has probably 60% to 80% infection, which is mind blowing. And hopefully as variants come along, that means the likelihood of severe sickness and death, that it’s not going to be as acute as it was in these big waves. We’re still learning about variants and many of these things I talk about, like getting diagnostic machines up broadly, getting the therapeutics out broadly, those things apply to this pandemic, and we should design a system that’ll work not just for this one, but for the future threats as well.

MODERATOR QUESTION: What, in your view, needs to happen to bring this pandemic to an end and ensure we never have a repeat of the suffering the world has experienced over the past two-and-one-half years?

BILL GATES: Well, sadly, many epidemics burn out, like Zika, because the number of people they can infect is simply the new birth cohort. And so we have a lot of endemic diseases at very low levels causing some burden, but not huge. Eventually, most humans will have broad enough protection from the various forms of COVID that there shouldn’t be a greater burden than we have typically with the flu, which of course, the flu comes and goes seasonally, and some years actually has a pretty big health burden, even when it doesn’t kill people. You know, like when pregnant women get flu, that’s not a good thing.

It’ll be endemic at some level. The therapeutics can help a lot. It may be the world will have to take a yearly respiratory vaccine that would include both flu and the latest for the coronavirus. There’s a big expense of putting that type of yearly vaccination in, including the elderly who are most at risk. But worst of this one is through, and the next one, when it comes, could be a lot worse because the death rate here was like 0.3% across all age groups. Now, 95% of that was focused on people over 50.

QUESTION from Dr Mercy Korir, Health Editor, Standard Media (Kenya): What is it about the health systems that we need to reorganize or rethink considering until everyone is safe, no one is safe? And from the experts that you’ve met, like Dr. Fauci, Dr. Tedros, what are some of the profound things that you think you have learned from them that would inform the rethinking of the health systems?

BILL GATES: Yeah, I wouldn’t say either of them are health systems people. Fauci is a vaccine researcher. But anyway, there’s a huge community of people where we look at health systems, particularly primary healthcare. Most of the benefit of a health system for the broad population in a developing country, by far, is that primary health care system.

There are countries that run extremely good primary healthcare systems even in times where their economy is not very large. There are parts of India, there’s Vietnam. Even in a lot of the more challenged African countries, there are places like Tanzania and Malawi, where vaccination rates are very, very high.

And so we look at the personnel system. We look at the training. We look at the data systems. Are people paid, does the supply chain work? And we do, we have very good data on the quality of health systems. The variance, even at identical income levels is super dramatic.

One of the areas I spend a lot of time on is talking with states in Northern Nigeria that we have partnerships with about improving their health systems because in many of those areas, vaccine coverage is well under 50%. There’s no reason for that. Every country should have an 80% to 90% routine immunization coverage. That alone is one of the best impacts in terms of saving children’s lives.

We have the resources we put into the system. We have the training. We have the culture of using data of making sure that the equipment and the supply chain works well. It’s almost like running a store where you have to have everything in place and then constantly monitor exactly whether that’s all working or not and have systems to fix it.

QUESTION from Teresa Clarke, Chair & Executive Editor, Africa.com: From what we’ve read about this book it kind of defines thought leadership. I mean, this is a grand concept that you have and a contribution to every person on the planet how to prevent the next pandemic. You’ve commented already about the global governance structures, that it would be the WHO and the UN who would need to implement this. Can you comment a little bit more? We’ve got this great blueprint. How do we implement it and how can those who believe in it, who do not work at the WHO, who do not work at the UN, what can we do to contribute to the world getting on board to try and prevent this tragedy again?

BILL GATES: Well, it’s very impressive that governments do quite a good job of protecting their citizens from certain problems. For example, fire is the one that most people understand because they see fire hydrants, they see fire departments. They often engage in training about safe practices if a fire alarm goes off. Over time, the deaths from fires has come way down, even though historically you had entire cities that would go up in flames.

The key there is full-time people and practice. I mean, they have okay tools like ladder trucks and axes and all of those fire hydrants, but it’s the alertness and the drills that take place. That’s why when I look at Australia doing so well, partly the scare of the SARS-CoV-1 made them think, okay, we have to get diagnostics quickly, and that means working with these commercial diagnostics companies, with these big PCR machines. And so by doing that and putting the right quarantine policies in place, they saved a lot of Australians’ lives, 90% who would have died if they’d been like, say, the United States.

It is tricky, as you say, because it’s got to be global, and who is in a position to help make this happen? Well, hopefully politicians realize that no country can protect itself. That is, there’s enough international commerce that it will spread and affect the world. Maybe 50% of the risk of an emergence comes off of the Continent of Africa, where you have lots of humans interacting with animal species. That’s what we saw with HIV and Ebola. Of course, with the flu and both SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2, it came out of Asia, so we have to be ready for it to emerge anywhere. But the quicker we see it, the better.

And so only a global organization can ask all the countries to do these exercises, asking them to report the data, and then understand, okay, for some of the developing countries, the global capacity will have to help them more. Whereas for the better off countries, it’s simply a matter of setting the standards and having the right communication to get the data constantly correct.

To me, in a way, because GERM is so cheap compared to the cost this pandemic, it feels pretty obvious that we should do it. But it’s not very often we add something at the global level. The WHO’s responsibility has not included having a significant full-time pandemic team. And so the foundation, as we haver un the polio effort and are the primary funder of that, we are building all that capacity.

Well, when polio gets eradicated, that capacity should focus on other diseases. And that’s partly why the GERM thing would be very, very timely.

QUESTION from Kenneth Igbomor, West Africa Correspondent, CNBC Africa (Pan-Africa): Listening to all that you have said so far, I’m just thinking about how we can set up the finance and ecosystems to notch up homegrown innovation especially for low-income countries.

BILL GATES: Well, a lot of the innovations are achievable without high technology, and some are very high technology. Running big Phase 3 trials about vaccines is an extremely complex thing. It’s like, do you want your jet engine to work in all circumstances? Understanding all of the different human diseases and variation to make sure vaccines are safe is ultra-complicated. The Gates Foundation has been the primary funder of getting manufacturers outside of the West funded so that they can create new vaccines. The way that we brought the childhood vaccine cost down dramatically was making sure there was rotavirus for multiple developing country manufacturers. And we made sure there was measles from multiple developing country manufacturers. We made sure there was pentavalent, and then the hardest was the pneumococcus.

It took a lot of non-market funding to get those vaccines to be created. As you know, it takes over 50 million for each new vaccine in terms of the Phase 3 trials. And the quality of the factory and the quality of the regulator involved is very important.

The foundation is the biggest investor in African regulatory capacity, both to approve drugs and eventually to be able to review drug manufacturing as well. Regulatory has been tough. We’ve been trying to get – the dream would be to have continent-wide regulatory alignment, but that’s been too difficult. What we’ve been funding is more regional alignment. We’ve been at that for now over 15 years and made some progress on both regulatory quality and alignment. There’s a lot more to do with that, which would be a necessary step to have the ideal situation, including the ability to look at manufacturing quality.

Over time, these capabilities are getting out there, but philanthropy and government plans have been part of that. If you look at the overall science plan and R&D plans for Africa, vaccines would probably be a priority in that.

QUESTION from Paul Adepoju, Freelance Writer (Pan-Africa): How can the continent be able to achieve self-sustenance and health security projecting into the next pandemic when it still has to rely on donor-funded, aid-funded vaccines for its citizens? What do you think can happen or should happen for Africa to be able to establish that level of independence, such that it is able to generate funds to procure vaccines from local production facilities?

BILL GATES: Yeah, well, it’s key to note that right now, the world has way more COVID vaccine supply than there is demand for COVID vaccines. In fact, even if the world could achieve 100% coverage, we have too much manufacturing capacity. Because so many of the vaccines succeeded, a number were funded, expecting maybe two-thirds of them would fail, most of them ended up being very good vaccines for severe disease and death. They did not end up being perfect vaccines to block infection. We’re working on a second generation of vaccines that have better duration, better infection protection and better breadth against new variants.

And so, because building up regulatory capacity in vaccine factories is like a decade-long thing, it was never very likely that, starting from scratch during the pandemic, that a new site would make any contribution to the global vaccine availability. In fact, Serum actually shut down their COVID vaccine manufacturing because there are simply no orders and there’s a lot of vaccines expiring all over the world. The limit to vaccine vaccination is not supply. It’s demand and logistics of getting these huge number of vaccines, which at least in some respects are very, very good.

The Gates Foundation, we do things to fund African science. We do things like agricultural productivity things or nutrition things that will play a role in improving productivity, and therefore, over time, economic strength. I’m not sure every country should make everything itself. I think there will still be intercontinental trade for some things, but the path forward is better regulatory science, better understanding of where the new market opportunities are.

There are some distributed manufacturing approaches where you could draw on the expertise of some companies, and they could put vaccine manufacturing sites in Africa. And at first, the expertise would not all be in Africa, but over time, you would transfer that. BioNTech’s been talking about that. We’re the only group that actually funds. We fund yellow fever vaccine manufacturing in Senegal. It’s not gigantic numbers, but it’s something that it’s a proof of principle that we got the regulatory and quality issues to be good enough.

I wouldn’t overfocus on vaccines, though. I mean, if you want to stop pandemics, diagnostics are way more important. It’s only once the pandemic gets out of control that then you go to vaccines. We have a lot of routine vaccines, and of course, the Gates Foundation is the biggest funder of the invention of a malaria vaccine, a TB vaccine and an HIV vaccine. And so, with distributed manufacturing, with better regulatory, some of those vaccines can be made in Africa.

My goal is that we have those vaccines exist. That’s the great tragedy, is not exactly where they’re made, but that there is no malaria vaccine. And it’s very strange how few partners we have in funding malaria vaccine work.

QUESTION from Ciku Kimeria, Africa Editor, Quartz Africa (Pan-Africa): I know after the 2014 to the 2016 West Africa Ebola outbreak, one of the big areas that the foundation was focusing on, especially when it comes to government preparedness, was supporting the establishment of emergency operations centers, something that I think happened in a few West African countries. And so, I’m curious now, with the rethinking of how to prepare for the next pandemic, especially after COVID, is this still something that’s being pursued, or will this change? Will the strategy for this change?

BILL GATES: Well, the so-called emergency operation centers is something that we have a lot of experience with, with our partners, because when we’re doing polio eradication work, we pull those together, sometimes at a national and sometimes at a regional level. And it lets you really coordinate the campaigns that you’re doing, look at your coverage, look at your refusals, look at your supplies, look at your hiring and your maps, and all the complex logistics that go into getting very high coverage.

And so, every country should have a plan that when there’s an outbreak, okay, where do they draw on people? Obviously, if there’s an outbreak in a few countries, there will be global resources that are coming in to help out, to the degree a country is willing both to do the drills to see, okay, where will we get the diagnostics, how would we set up quarantine policy, how would we communicate. And when the real thing is coming in, there’ll be immense global resources to try and prevent the spread to the entire continent or even to every country in the world. The basic approach is there.

Our focus, we always look at lives saved, and lives improved in our work. For us, our biggest story is malaria, and HIV and polio, but we found ourselves building some of the infrastructure things like CHAMPS, which is a minimally invasive autopsy to see what causes of death is, CAMSA, which is a statistical approach to seeing what the disease burden looks like. We’ve ended up funding a lot of basic infrastructure, which ideally, the global health endeavor would be funding those things, including the overall summary, which is called the Global Burden of Disease, which is primarily funded by us.

QUESTION from Linord Moudou, Health Reporter & Host, VOA News (Pan-Africa): When we are dealing with outbreaks such as polio, measles or Ebola, scientists already know what they are and what to do, and they also have the tools to tackle them, be it prevention or treatment. Some of the earlier challenges with COVID was the fact that scientists had no knowledge of the virus itself, and they are still actually learning as the pandemic progressed. And what is the best-case scenario to prepare when it is a new disease and scientists have no knowledge on it?

BILL GATES: Well, the greatest risk by far is viruses that are spread human to human in respiratory. And there’s three big virus families that do that: Measles, we’ve learned a lot about; smallpox, of course, we were able to eradicate; flu was probably the one people were most worried about because of the 1918.

These coronaviruses have been studied. There are coronavirus diseases in chickens. We do vaccines for chickens for a form of coronavirus, and that was one of the sources of the crazy rumors that we had some patent on a coronavirus, which was actually a chicken coronavirus that one of our grantees filed, but it was about saving the lives of chickens.

The way that respiratory viruses work, they have to latch on to upper respiratory tract. And so, we can understand, can we get the upper respiratory tract on high alert? Can we get the innate immune system through some pathogen-independent drug to be ready so that, say, for 90 days, you’re very unlikely to get infected? Likewise, because of it’s got to be respiratory, things like masks, like distancing, those are going to apply to whatever this new pathogen is.

But as you say, it might surprise us. That’s why we have to go and sequence it. We fund a thing called Geyser (ph), which is getting sequencing capacity in Africa to be adequate, and that’s worked very well for the COVID work. The foundation was the only funder of the trials of the vaccines in Africa, and that was to build their safety credibility, and also to have a group of patients who are living with HIV and understand where there are special considerations about the vaccine there. And as part of that, those trials a lot of capacity was put in place. And now, the variant sequencing work has been done reasonably well in different parts of Africa. But yes, we have to accept that we might get surprised.

We benefited that SARS-CoV-2 COVID was a lot like SARS-CoV-1. The spike protein is very similar. And so, the fact we had a vaccine candidate, we did the sequence, and we had a vaccine candidate within 30 days. Part of that was that we’d seen a fairly similar virus and done some work on that before.

QUESTION from David Thomas, Africa Business Magazine (Pan-Africa): What role can technology play in future pandemic planning and forecasting in Africa? And how does Africa stand in relation to other countries, other regions, in its adoption of the technologies that can help with the next pandemic?

BILL GATES: Well, the disease modeling work that the Gates Foundation funds started because of our work in malaria and polio. We wanted to know where we were going to get polio outbreaks, and we wanted to understand what set of interventions would lead to actual successful malaria eradication. A lot of failed efforts at malaria eradication had taken place in the past. And so, we thought only by having really strong models for this would we understand what was necessary.

Now, we’ve generalized those models to things like HIV and TB. We’ve made those open source, and we have a lot of collaborators in Africa who take the base model work we do, and they put their data in, their assumptions in. And so, particularly in HIV and TB, we’ve had some great collaborations. With malaria, some of that’s with Swiss Tropical. But models can help you understand risks and realize should you try to do an eradication or not.

The capacity for this type of work, it’s mainly the universities. And so, South Africa stands out as having somewhat more of this expertise, but it’s as you get medical universities with public health programs that then you have people who can take the base level stuff that we make completely free – this is open source completely – and play around with it.

One thing it’s shown us is it’s going to be hard to get rid of malaria, and that’s partly why you hear us being such advocates for tools like Gene Drive that can reduce mosquito populations, Anopheles mosquito populations, because our simulation shows we really need to knock, at least for about three years, knock the mosquito populations down before we could possibly do eliminations in the tougher areas, including DRC and Nigeria.

The modeling stuff is a shared resource, but the strength of the universities will determine how much that gets exploited.

QUESTION from Mayowa Tijani, Development Journalist, The Cable (Nigeria): You said in your recent TED Talk that your warnings about the pandemic in 2015, that 90% of people who have listened to that video listened to it after the pandemic. And, of course, we had to pay a lot for not listening. And now, of course, you’re raising an important question for the world at this time. Do you think the world is listening to you this time around?

BILL GATES: It’s hard to say. The world has a lot of challenges. You’ve got the war in Ukraine, you’ve got unrest in Ethiopia, you’ve got unrest in other parts of Africa. It’s not a simple situation, and sadly, the world’s going through a bout of inflation, particularly or food prices and fuel prices. We’ll see fertilizer costs go up, and we’re super worried that that means a lot of African farmers will use less fertilizer. And then that means you have less food a year from now, and that can be self-reinforcing.

It’s not like, even for the foundation, we’re only working on pandemic preparedness. We’re still working on nutrition, and HIV and malaria, but given that it cost trillions and that the investment to avoid this is just billions, it seems like the most obvious thing. And after we had world wars, we did work. We created the United Nations and lots of ways that fortunately, have minimized at least the larger wars since that was over.

And so, I do expect the debate during the next year to take some of my ideas and other people’s ideas and say, governments ought to their citizens, like they prepare for earthquakes or fires or war, that they need to do this. The rich countries were deeply affected. And so, the financing for the GERM, the financing for the innovation and even some of the financing for the health systems should come from the rich countries, but I can’t guarantee it because they have so many priorities and the pandemic stretched their budgets in an extreme way. And now, with Ukraine, they see all the demands coming out of that in parallel.