Nigeria recently celebrated a full year and a half without a new case of wild poliovirus. The World Health Organization (WHO) has certified there has been no evidence of wild polio in Nigeria for more than a year and removed it from the list of polio-endemic countries. These are milestones both for Nigeria and for the global campaign to eradicate polio. Nonetheless, continued effort and vigilance will be critical over the next two years to declare the country and the rest of Africa completely free of the disease.

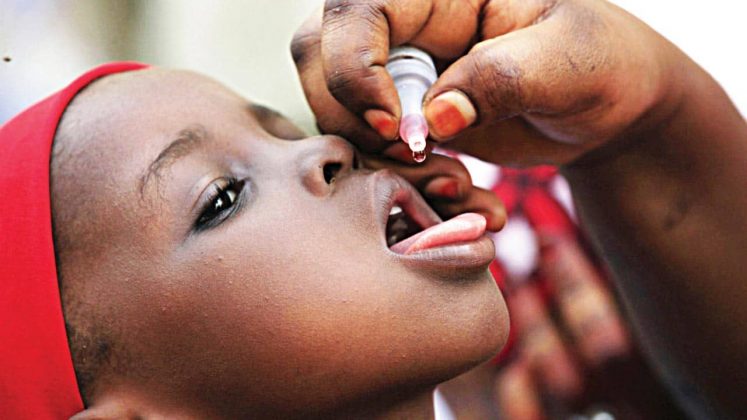

Toward these ends, Nigeria has significantly increased polio immunity among its population over the past three years. As recently as February 2012, only 16 percent of local-government areas (LGAs) in high-risk states had achieved the target level of immunity coverage: vaccinating more than 80 percent of all children under the age of five. By September 2015, coverage had improved more than sixfold: 97 percent of LGAs in high-risk states had achieved the target (Exhibit 1). The success of Nigeria’s federal and state governments, Global Polio Eradication Initiative partners, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is all the more impressive given the climate of disinformation, intimidation, and violence that peaked with the 2013 murder of 13 vaccinators by insurgents in Kano and Borno states.

This article reviews the steps that Nigeria and its partners took to eradicate polio, especially the introduction of a novel approach to disease control: emergency operations centers (EOCs). It also explores what the lessons learned from Nigeria’s approach to polio might teach other countries about emergency health responses.

Taking the fight to polio in Nigeria: Establishing EOCs

In 2012, Nigeria had a serious polio problem. It was Africa’s only remaining polio-endemic country, and the number of confirmed new wild poliovirus cases was increasing, eventually reaching 122 that year. Indeed, Nigeria was considered the worst performing of all polio-endemic countries, with a majority of new cases throughout the world. Immunization coverage was declining, attributable to weak program performance, lack of accountability, significant levels of mistrust at the community level, poor engagement of the country’s traditional structures, and little coordination between the government and its international partners working to eradicate the disease. In addition, the states with the highest risk for polio were all in northern areas plagued by weak health systems, poor health indicators, and challenging security conditions.

Nigeria created a presidential task force to lead the country’s response to the eradication of polio. The plan was to work with national and international organizations, such as the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA), WHO, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and Rotary International. With the support of the Gates Foundation and strategic assistance from McKinsey & Company (see sidebar “McKinsey’s support for Nigeria’s polio-eradication effort”), the Ministry of Health created EOCs to focus on the highest-priority interventions, to improve coordination, and to manage the program’s overall performance closely. EOCs are centralized command-and-control units responsible for disaster preparation and management. Other countries and cities have also used them to respond to emergencies.

Nigeria’s National Polio EOC was established in the capital, Abuja, in October 2012. The EOC model requires national and international organizations to locate their leaders in the same place and to meet regularly to develop and execute eradication strategies, improve vaccination campaigns, and respond immediately to outbreaks. Each organization contributed people to support the collection, analysis, and reporting of eradication data. The NPHCDA provided local staff to gather data from LGAs, wards, and settlements in high-risk states.

The Minister of State for Health, Dr. Mohammad Ali Pate, asked the NPHCDA’s Executive Director, Dr. Ado Jimada Gana Muhammad, to lead the creation of the national EOC. He appointed Dr. Andrew Etsano as EOC Incident Manager and Dr. Faisal Shuaib as Deputy Incident Manager, with direct reporting lines to the Executive Director and the Minister, respectively. They worked with the NPHCDA and the international partners to develop the required organizational structure, working committees, meeting routines, procedures, and data-analysis support. Besides establishing the national EOC in Abuja, the ministry oversaw the design and set up the first state EOC in Kano. This became the model for the successful EOCs opened in six other high-risk states in northern Nigeria.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Scott Desmarais is a principal in McKinsey’s Lagos office. Since November 2012, more than 25 consultants from McKinsey’s offices in Lagos and around the world have supported Nigeria’s efforts to eradicate polio. The author wishes to thank each of them for their commitment and passion.